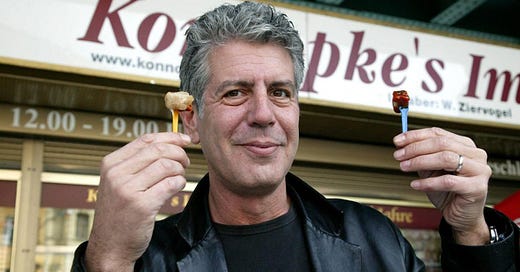

Anthony Bourdain liked Montréal. He spent enough time here where some might say—though not intentionally—he raised awareness of the city’s culinary scene in the early 2010s, to Americans at large. He seemed to genuinely appreciate the city’s fare, and he was appreciated by local restauranteurs. After all, there’s murals of him painted on the sides of Montréal restaurants, and he was openly embraced by the Joe Beef brain trust early on. Though he never lived here, for some reason, he had a strong bond with Canada’s second-largest city.

On a lazy Sunday morning recently, I found myself re-watching his 2011 Montréal visit on The Layover. The show’s premise is essentially a food tour taking place during a 48 hour layover in a city, with aims of highlighting standout spots—both high and low brow—in a rapid pace with a tickling clock breaking up the segments. During the Montréal episode, while contextualizing the city’s place within the country, Bourdain says, “Without Montreal, Canada would be hopeless. It's where the cool kids hang out."

I might be inclined to agree with the first part—without Québec, without Montréal, I can’t imagine Canada and the cultural vacuum left by such a thing. I mean, I’ve lived in Montreal for 9 years on and off, for many reasons — the local food scene that Bourdain loved, being a very big one. But what I love about Montréal, and Québec writ large, is that it doesn’t feel like Canada; it feels otherworldly, as its own thing. Québec is a recognized distinct nation after all, and that sense of foreignness—the feeling you get when you first travel abroad, where everything is just slightly different—still lingers for me here.

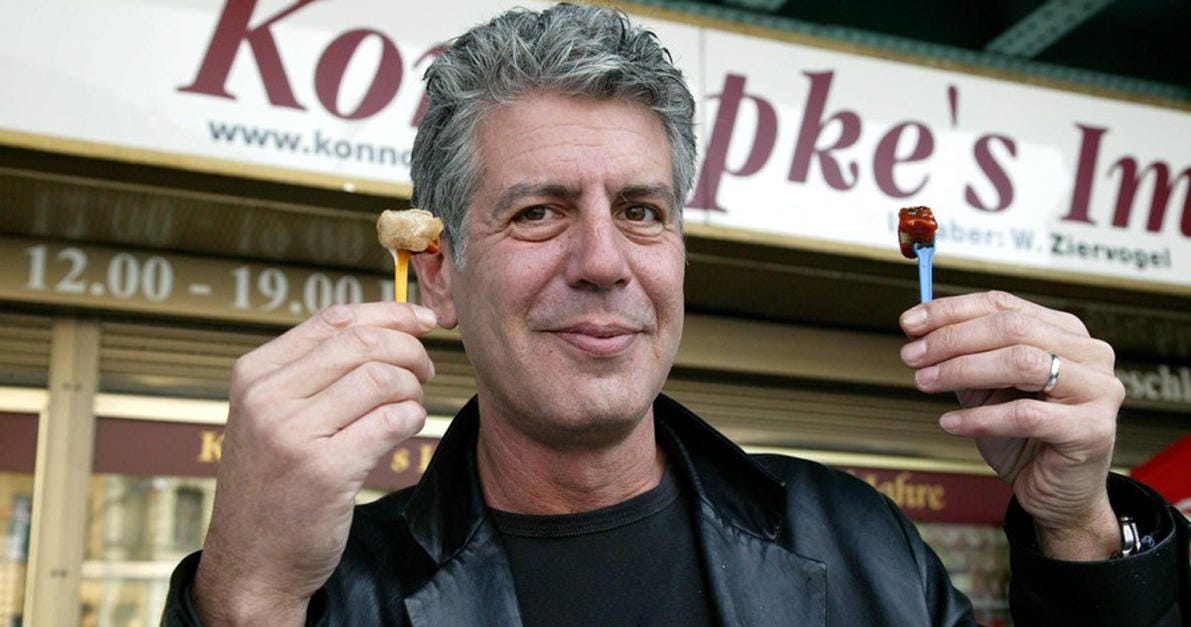

While watching the Montréal episode of the show, I noticed a local cookbook store owner was hired for the day to take Bourdain around to a few spots, chief among them the famous Jean-Talon Market. I said to myself, “That’s the guy from the cookbook store I frequent in Westmount,” albeit his 13 years younger self. His shop is called “Appetite For Books,” an incredibly well curated cookbook store of about 500 sq ft., a real gem if you’re a food-obsessive like me.

The owner is a bit dorky, and can come across as aloof or standoffish depending on the day, but once you get him talking, he’s actually fun to nerd-out with about all things cooking. I went back recently and asked him what it was like to spend an entire day with Bourdain during the height of his popularity, as a tour guide of sorts. He told me that the show’s 48-hour timeline and ticking clock seemed accurate, as producers tried to corral Bourdain in and out of taxis, bouncing from place to place. The scene where he eats breakfast at Beauty’s was actually shot in the morning, right before he met with him.

I guess, in a perverse way, I wanted to hear from someone who knew Bourdain. This guy was reluctant to talk about him, and he said since his passing he isn’t able to watch any of his TV shows—understandably so. I think it’s not easy for a lot of people to watch Bourdain post-suicide, especially if you can see under the veneer of his television persona: he was world-weary, dark, pessimistic, funny, optimistic too, and towards the end, very depressed. He was, above all, an incredible story teller. The cookbook store owner told me that Bourdain was basically exactly like he is in the shows— a bit cantankerous, an astute observer, polite, but also very shy. I knew he was shy, and that he hated the limelight. He drank a lot, and of course, he ate a lot.

Bourdain first came on my radar around 2010 or 2011. I visited a friend in New York City around that time and we decided to trek up to Spanish Harlem to get burgers from a Bourdain-approved spot. The contrast from his West Village neighbourhood to that of Harlem was stark. It was summer and we noticed everyone was out, big families were hanging around, laughing, kids playing—everyone seemed happy. In the air you could smell BBQ, marijuana, garbage, diesel fumes: New York trademarks. You heard music booming and people speaking Spanish amidst big apartment blocks and crowded side streets.

The burgers were good, I guess. But the neighbourhood vibes left a bigger impression on me. Bourdain or his producers were always looking for a story, and the one they wanted to tell wasn’t through the lens of tourist traps or easy-to-access restaurants. Yes, he ate at Michelin-adjacent tweezer-places, but he was more himself sitting on a wobbly bar stool, or a plastic patio chair on an ad hoc street food patio. This hole-in-the-wall Harlem burger joint later became emblematic of a “Bourdain spot”. Simple, honest food. Unpretentious.

The biggest reason why I like Bourdain is because he advocated for dialogue. When he visited countries historically hostile to Americans—like Vietnam or Iran—he sought to sit down with the locals and understand their experiences. He believed food could bring two opposing sides together. He would 'break bread with enemies' to see where and how he could connect with someone so different. It was an exercise in humility: you're not that bad; I'm not better than you. We can find some common ground—especially through food—or something like that. How can you heal, how can you avoid conflict, if you can’t talk to “the other side?” Politically, in 2024, this idea is an impossibility—laughable even.

On another trip to New York City, while out in Queens eating at New Park Pizza, I talked to a Trump supporter in the parking lot. I didn’t know his political allegiances at first; it only came up about 20 minutes into our conversation. We were lingering in the parking lot, talking about the Vespa scooters and cars parked nearby. This guy just seemed like a nice person who, like us, was out to eat some tasty slices. Food brought us together. If he had been wearing a “TRUMP 2020” t-shirt, or some outwardly way of being identified as a MAGA Replubican, it wouldn’t have stopped me from talking to him. But that’s just me. Maybe it would have been Bourdain’s position, too? Not all Trump supporters are scumbags.

Life is more interesting if you’re open; you never know what you’ll learn from simply being open to talking to someone different, someone very different. Maybe it will reinforce your prejudices, maybe it will be yet another missed opportunity to truly connect and empathize. Maybe it will add more protective layers to your shell, reinforcing your personal—and algorithmic—bubble, closing you off even more. You become completely calcified, clinging to your views in a death grip. We’re all prone to tribalism, even those of us who pride ourselves on having 'open hearts and open minds.' I guess I still struggle, all these years later, to understand how some of my friends, cohorts, family, and colleagues—with the most progressive views on paper—can be the most closed-minded people in real life. But I digress.

“A man’s work is nothing but this slow trek to rediscover, through the detours of art, those two or three great and simple images in whose presence his heart first opened.” - Sartre

On yet another trip to New York City this past April, I headed uptown again. This time to the Upper East Side to visit “Kitchen Arts & Letters,” the be-all-end-all of cookbook stores. Any cuisine, any obscure weird cookbook you can think of, is available here. It was overwhelming for me, because I really, really like cookbooks. I prefer referencing cookbooks over the internet, and I’ve amassed a small collection over the years.

But I don’t follow the recipes per se, nor do I follow step-by-step directions in my NYT Cooking app. For me, written recipes are simply a tool for some inspiration and guidance. I’m more left-brained and creative and enjoy developing my own; I don’t like to paint inside the lines unless I’m going to “bang out a classic,” but this is so boring (to me). So whenever I’m in a bookstore or visiting someone’s apartment, if I see cookbooks, I instinctively check them out.

Cookbooks are better than the Internet for a million reasons. They’re the product of blood, sweat, and tears, created to be lasting references and artifacts for home cooks. Unlike recipes on an iPad screen, cookbooks don’t have pop-ups, ads, clickbait titles, or obnoxious sponsors and endorsements. They’ll remain relevant long after a recipe blog du jour is retired to a server, buried deep in Google’s indexes.

Cookbooks are inherently immune to gimmicks. When done well, they become sought-after objects, passed down, shared, and gifted. Don’t get me wrong—I still look up recipes online all the time, but it’s done hastily, and I don’t fuck around. I go straight to trusted sources. Though I’m not a big baker, I do use the Internet for baking recipes more often, but thankfully I’m now at a level where I’m able to improvise, so I’m not necessarily bound by Google results.

People often say Bourdain had a dream job. It seemed that way when he was sitting in a hammock by the beach, rum cocktail in hand after a long meal, waxing about the bad optics of corporate beachfront developments. I still don’t think I would want to have a job like Bourdain’s. My dream job would be something like a full-time recipe developer, eventually channeling my cooking experience into a cookbook of sorts. This could be fun. But does the world need another cookbook?

Much like the Internet, the physical world is filled with shitty recipes from shitty cookbooks. Go to any thrift store’s book section and you’ll see a graveyard of forgotten, crummy cookbooks from the 70s, 80s and 90s. When I spoke with the owner of the local cookbook store I mentioned earlier, I asked why there are so many bad cookbooks in the wild. He told me that of the hundreds of cookbooks publishers pitch him each month, he might buy only 1%—sometimes even less.

That means 99% of new cookbooks don’t meet his standards, suggesting that publishers are dishing out cookbook deals left, right, and center. He explained that part of the reason is they tend to sell well for publishers, even 30 years into online recipe culture. But many inevitably end up on Salvation Army shelves or collecting dust atop your microwave.

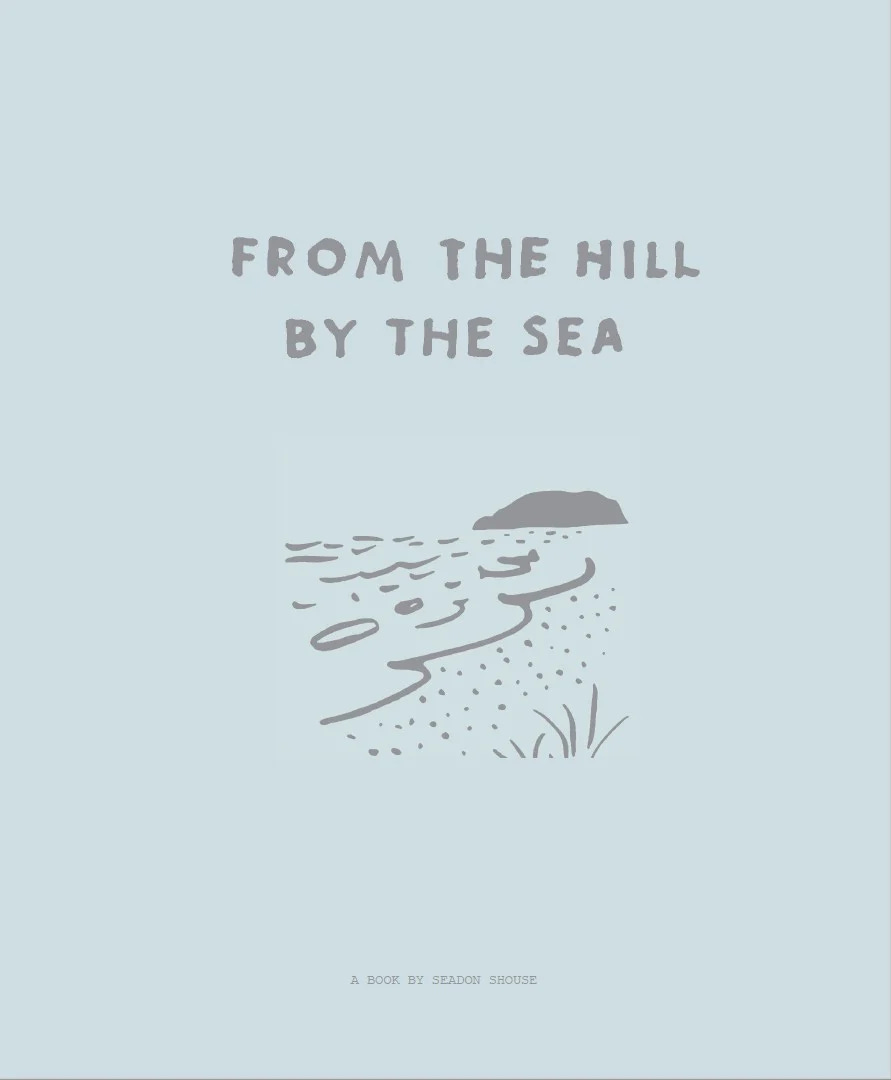

While browsing the cookbooks at Kitchen Arts & Letters, feeling completely overwhelmed, I found about ten titles that piqued my interest. I asked the clerk about cookbooks that he recommended, or titles that were popular among his customers, and he suggested “From The Hill By The Sea,” from Chef Seadon Shouse of Halifax Restaurant. I hadn’t heard of this chef or his Hoboken restaurant before, but as someone who grew up in Halifax and is fond of seafood, I was intrigued by the idea of this book.

The clerk told me that Shouse self-published the book. A lot of chefs and food writers in New York City were championing it. The book's binding cloth, photos, font, layout, writing, and recipes are all simple, clean, and honest. Everything is tastefully presented with a Nova Scotia theme that feels deeply familiar to me. Familiar food is comforting, and flipping through From The Hill By The Sea reminds me of my family and the food of my youth. After nearly three hours in the cookbook store, chatting with the clerk about all things food, I finally paid for my book and left. I could have easily stayed longer.

After leaving the bookstore, I realized I was relatively close to Harlem, so I went back for the first time since eating those Bourdain-approved burgers some 13 years earlier. I ended up at Patsy’s for a quick, quintessential New York plain cheese slice. I think Patsy’s has been around for almost 80 years.

At a red light a guy in his car was blasting Cam’ron at deafening volume, a song from the “Purple Haze” album. When it turned green he shot off down Lennox Avenue at breakneck speed. So Harlem. Looking for the subway, I glanced around and suddenly realized I was in a whole different world, having just come from the well-to-do Upper East Side. Sometimes that chaotic, frenetic New York energy has a way of jolting you awake, pulling you back into the Matrix. You can’t really zone out for too long—the sensory overload is real.

A few days later, my good friend took me to New Jersey (where Bourdain grew up) to shoot guns at a range and eat burgers—does it get any more 'American'? He took me to an absolute gem called 'White Mana,' which is famous for their sliders, a place that Bourdain knew and enjoyed—the food of his youth. It was a welcome escape from the hyped-up spots in Brooklyn and Manhattan, where influencers and the social media hamster wheel often creates long lines by putting them on blast.

The sliders were incredible, but just driving around New Jersey in my friend’s 90s BMW was even more fun. If it doesn’t sound fun to you, it’s probably because you’re not middle-aged. I’ve already done everything a young man does in New York City. Nowadays, I don’t want Michelin-starred dinners in Manhattan, staying out until 4 a.m. at 'cool' bars in Brooklyn, or expensing brunches on my work credit card.

When I travel now, I just try to be open, be present, talk to people, and eat honest food. I don’t try to be like Bourdain at all. I don’t try to be like anyone—that’s a young person’s game. I know who I am and what I like. I’m happiest when I get to travel and find inspiration to bring back to my own kitchen, which is, ultimately, my happy place. This is all you can do in life. Find what makes you most happy. As long as it doesn’t hurt anyone, you’re good.

I don’t get sad when I see Bourdain on screen. I think about how he made people feel—usually good, sometimes humbled. He was a storyteller and a writer. He made you question your choices: Why are you eating here? Why are you staying there? What is the local economy comprised of, and where do you fit in as a tourist? Don’t be a shitty tourist.

Of the countless Bourdain wannabes that now clutter the online food space, the ones who ruin eateries by merely mentioning their name, who have nothing meaningful to say, I find no inspiration. I’m not saying we should gatekeep, but I am saying that there are no more voices like Bourdain’s. This, to me, is more sad than his passing.

Despite his influence on so many, all we see now are TikTok food influencers just trying to monetize their travels without any compelling stories to tell. It sucks. I guess that’s why I watch No Reservations and The Layover reruns—I’m trying to catch a vibe that doesn’t exist anymore. Maybe this is my own bubble I’m retreating into, and maybe I need to open up more to a changing world, and a rapidly evolving food scene? All I know is, there will never be another Bourdain. And that’s OK.

In memory of Anthony Bourdain, 1956-2018